Sally Weinrich knew something was terribly wrong. On two separate occasions, she forgot to pick up her grandkids from school, and she kept mixing up their names. The 70-year-old retired nursing professor had to face reality. Her worsening symptoms — the forgetfulness and confusion, the difficulties communicating and organizing activities — weren’t just stress or the normal wear and tear of aging. She lived in a matchless setting, on a lake in South Carolina, nestled in a bucolic wood. She swam daily and kayaked three days a week. But even her purposefully healthy lifestyle couldn’t protect her from the darkness she feared most: Alzheimer’s disease.

In 2015, imaging tests revealed the presence of amyloid plaques, the sticky proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease that collect around brain cells and interfere with relaying messages. Weinrich also eventually learned she carried the ApoE4 gene, which increases the odds of developing Alzheimer’s. The disease was diagnosed after a neuropsychological evaluation. “I felt a total sense of hopelessness,” recalls Weinrich, who sank into a deep depression. “I wanted to die.”

Shortly after, her husband heard a radio program about a new treatment regimen devised by physician Dale Bredesen that seemed to reverse early stage Alzheimer’s. The couple contacted the UCLA professor of neurology. Bredesen told them that, based on nearly 30 years of research, he believes Alzheimer’s is triggered by a broad range of factors that upset the body’s natural process of cell turnover and renewal; he didn’t think it emerged from just a handful of rogue genes or plaques spreading across the brain.

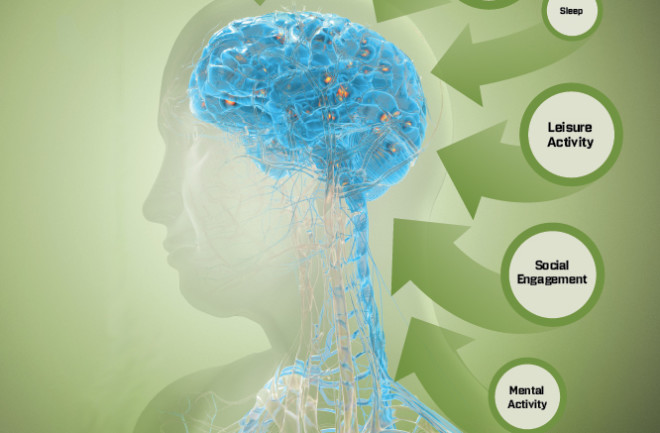

Bredesen has identified more than three dozen mechanisms that amplify the biological processes that drive the disease. While these contributors by themselves aren’t enough to tip the brain into a downward spiral, taken together they have a cumulative effect, resulting in the destruction of neurons and crucial signaling connections between brain cells. “Normally, synapse-forming and synapse-destroying activities are in dynamic equilibrium,” explains Bredesen, but these factors can disturb this delicate balance.

These bad actors include chronic stress, a lack of exercise and restorative sleep, toxins from molds, and fat-laden fast foods. Even too much sugar, or being pre-diabetic, heightens risk. “If you look at studies, you see the signature of insulin resistance in virtually everyone with Alzheimer’s,” he says. “If you look at all the risk factors, so many of them are associated with the way we live.”